UEC Profile: Jennifer Delamere, Scientist of the Arctic, Albedo, and Snow

Published: 22 November 2021

In a whirlwind, complex career, one researcher studies arctic weather and climate at scales tiny and vast

Editor’s note: This is the eighth and final article in the 2021 series of profiles on members of the ARM User Executive Committee (UEC).

“I want to go there.”

That’s what eighth-grader Jennifer “Jen” Delamere said one day in 1985 as she watched her father’s home movies of his epic road trip to Alaska. Before her eyes, on the screen in their New Hampshire living room, snow-capped peaks flickered to life, moose towered in dense shrub, and bears loped in the distance. Above all, there were views of the rugged immensity of what is now Denali National Park and Preserve.

And she did go there.

Delamere by now is a veteran student of the arctic environment, snow science, and the atmosphere―an associate research professor at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks (UAF). She is busy these days assisting on a project calculating the changing albedo—reflectivity—of snow and other surface features during spring snowmelt events.

She is also an instrument mentor for the Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) user facility, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). She keeps track of a suite of instruments related to Alaskan precipitation and snow depth.

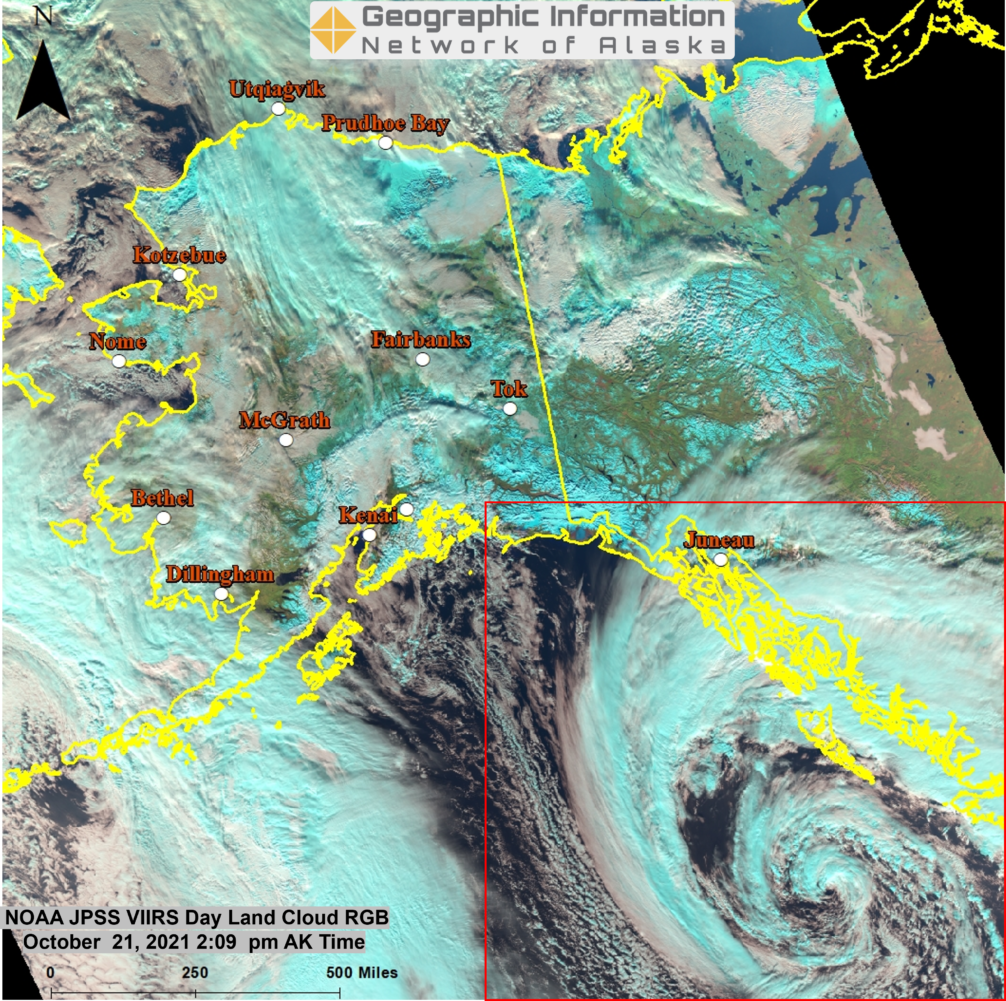

Another of Delamere’s jobs is to direct the Geographic Information Network of Alaska (GINA), a satellite direct-broadcast facility at UAF.

GINA allows her to see near-real-time imagery of Alaska from space every day, including the swirls of developing storms and, in season, the blurry drama of wildfires. GINA harnesses imagery from polar-orbiting satellites. The images are astounding, says Delamere—so much so that “to see it all, every day, live” makes it hard to look away long enough to write code.

That’s another day job: She is part of a multistate team continually improving the computational speed and accuracy of high-performance broadband radiation code for the rapid radiative transfer model (RRTM).

Developed first in the 1990s, RRTM is now in its third generation. Delamere has been part of the model’s development from the beginning. She works with a version called RRTMGP. (The “G” indicates that the version is used in global climate models. The “P” is for parallel processors.)

“I love Alaska,” says Delamere, “and I love a computer.”

‘Wide-Ranging Perspective’

Delamere points to her many “hats” (snow researcher, instrument mentor, radiative transfer modeler, GINA director) as proof she will add depth to an advisory group she joined in January 2021: the ARM User Executive Committee (UEC). Members serve as liaisons between data users and ARM management.

She is joined by veteran ARM data users who are experts in cloud microphysics, atmospheric aerosols, modeling, deep convection, and other research specialties. Delamere leads the UEC subgroup for enhancing communication with the satellite community and is the committee’s vice-chair. In 2023, she will take over as UEC chair.

“I have a wide-ranging perspective,” says Delamere. “That allows me to see ARM in many different ways.”

It helps, too, that Delamere has been part of ARM data-gathering for so long. She was still an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins University (B.S., physics, 1993) when she spent the summer of 1992 as an intern at UAF.

“I never looked back after that,” says Delamere of the impulse to study in Alaska, inspired in part by her father’s home movies. “It’s been everything arctic ever since―and the Arctic is never the same place twice.”

To add to her ARM credentials, she was still in graduate school at UAF when she attended her first ARM meeting in 1994, in Charleston, South Carolina. At the time, Delamere worked with UAF’s Knut Stamnes, the initial site scientist for what in 1997 became ARM’s North Slope of Alaska (NSA) atmospheric observatory at Barrow (now Utqiaġvik).

She also worked with the NSA’s first site manager, Bernie Zak, then at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico. (Zak is now at New Mexico State University; Stamnes is at Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey.)

For her doctoral dissertation work, Delamere helped design the data quality control scheme for the NSA, a site intended from the beginning to collect data on cloud and radiative processes at high latitudes.

“I’m a veteran,” she says. “ARM has touched everything I have done.”

SALVO Targets Albedo

GINA and software development often keep Delamere bottled up indoors. But her other two jobs—the snow project and the instrument mentorship—sometimes get her outdoors. There, to her, snow and cold and the scenic drama of Alaska are heaven-sent.

Delamere is a co-investigator on Snow ALbedo eVOlution (SALVO), an ARM field campaign that is part of a related project funded by DOE’s Atmospheric System Research (ASR).

Led by UAF geophysics professor Matthew Sturm, SALVO is an investigation of snowmelt where land, sea, and sea ice join in northernmost Alaska. Every spring, melting snow drives a transition in the arctic landscape. Covered in ice nine months a year, the landscape flips within two weeks to a patchwork of darkening tundra, bare ice, and spreading ice ponds.

Delamere, Sturm, and others scramble to record the nature of that transition, especially its changing albedo. That’s the degree of the reflective whiteness of a landscape or built surface. (“Albedo,” in Latin, means “whiteness.”)

When covered in ice and snow, the arctic landscape sends about 80% of solar energy back into the atmosphere. When dominated by dark tundra and open water, that cooling effect is four to six times lower―which has consequences for planetary temperatures on a global scale.

“We’re trying to understand the springtime melt season in the context of radiation,” says Delamere, who will join her colleagues starting in April 2022 for another round of fieldwork. For six weeks, at or near the NSA, they plan to set up instruments on tundra, lagoons, and sea ice to measure the changing albedo of the changing terrain.

Through NSA instrumentation, “ARM provides the atmospheric column,” including contextual measures of temperature and humidity, she says. “SALVO looks down at the snow and tundra surfaces.”

So far, the SALVO researchers have documented only one spring, in 2019. In the two years since, fieldwork did not happen because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

‘Digging Down’

During the 2019 round of fieldwork, Delamere and others blocked out a transect 200 meters (656 feet) long and 25 meters (82 feet) wide for measuring albedo; created a high-resolution map of snowmelt using a camera mounted on a pole; and dug survey trenches in the snow.

In spring 2022, they will collect data “in much more detail,” she says. “How water flows through the snow will be our focus now.”

That means mapping the flow of liquid water underneath and through the snowpack, which in turn heavily influences the surface’s changing reflectivity.

“We keep coming back to the water,” says Delamere.

Also on the menu for spring 2022 is an attempt to survey albedo on “many more surface types,” she says, including willowy tundra grasses with gradations of color that affect reflectivity values. “Brown is not always just brown.”

A catalog of what they see on the north shore will create data transferable to other arctic landscapes.

At times, those landscapes are marked by “crazy-wonderful snow forms,” says Delamere, and by bands of horizontally blowing snow that “move like ocean waves.”

More snow beauty came her way in 1995, during a National Science Foundation sea-ice cruise to Antarctica aboard the R/V Nathaniel Palmer.

In the 1990s in Barrow, Delamere did pre-cruise work for the first arctic field campaign in which ARM participated: Surface Heat Budget of the Arctic Ocean (SHEBA). The 1997–1998 effort set an instrumented Canadian icebreaker adrift in the Arctic Ocean ice pack for a year. ARM and NOAA contributed instruments, data, and personnel to SHEBA, primarily funded by the National Science Foundation and the Office of Naval Research.

If there is not much snow, cold alone is attractive to Delamere. In 2009, she participated in the chilly second phase of ARM’s Radiative Heating in Underexplored Bands field campaign (RHUBC-II) on Cerro Toco, a mountain in Chile’s Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on Earth.

Keeping Watch

Though burrowing into the snow is not the order of the day, Delamere takes occasional forays outdoors as an ARM instrument mentor.

“ARM data are very important for the work we do,” says Delamere, calling measures such as temperature, wind speed, humidity, and precipitating clouds important for “putting together pictures of day-to-day weather.”

She is an associate mentor for several instruments. “Mentor” is ARM-speak for monitoring the performance of outdoor sensors and the quality of their derived data.

With Sturm as the lead mentor, Delamere helps keep an eye on the NSA’s sonic ranging sensors, box-like devices the size of a digital camera that measures snow depth and water levels. At prescribed time intervals, they send out an ultrasonic pulse, then measure the time it takes for the pulse to hit a target surface and return.

She and Sturm also look after the NSA’s laser disdrometer, a Y-shape instrument that looks like two roadside mailboxes facing each other. It classifies precipitation types and measures drop/particle sizes and fall speeds.

In addition, Delamere assists Sturm with a solid particles mass flux sensor (SPMF), which also collects wind-speed measurements.

Pointed at the SPMF, as well as a nearby NSA instrument called the ultrasonic 3D anemometer, is a camera intended to monitor surface conditions at the site. It snaps five different images every 15 minutes and then generates movies every 24 hours from all the images. The result is the tongue-twisting ARM Camsonicwindspmfmovie.

“It’s wicked fun,” says Delamere, who this fall enjoyed seeing migrating birds across the tundra. In winter, she marvels at wind-borne surface snows forming wedding-cake drifts and icing up instruments.

Oh, that: icing.

“It’s very hard to keep instruments rime- and ice-free,” she says. The camera is a great guide to see what gear needs de-icing and which iced-up instruments can be correlated with unusual datastreams.

From Digging Fork to Ice Ax

It could be argued that a quite different instrument inspired Delamere, in her childhood, to dream of Alaska: a four-tined potato fork, with tines bent at 90 degrees to dig root vegetables.

Every fall, she and her family would caravan from their home in seaside Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to an ancestral spread in Portage Lake, Maine. Delamere’s great-grandfather was a Maine wilderness guide before the Great Depression drove him to find work at the Kittery shipyards in the southern part of the state. Her great-grandmother grew up in a “rough frontier life,” she says, which in the next generation inspired annual trips north to glean potatoes and to live, however briefly, a simulacrum of olden days. “That was my draw to Alaska.”

It helped, too, that the same great-grandmother, whose dirt cellar in New Hampshire could store a yearly haul of 10,000 pounds of potatoes, had a weakness for television documentaries about Alaska.

Given those early influences and desires, it may seem counterintuitive that Delamere, at age 17, enrolled at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, Maryland. But that was another adventure: city life for a small-town teenager whose only other urban experience was nearby Boston, “where I snuck to when my mother told me I couldn’t,” she says.

Delamere studied physics at Johns Hopkins―astronomy, at first.

“I wanted to touch a star,” she says.

The internship in Alaska as a rising senior changed all that. In the fall of 1993, Delamere joined UAF’s PhD program in atmospheric science. She traded her potato fork for hiking gear, quickly hewing to a version of the frontier life during treks into the mountains.

Delamere has a 1995 photo of her cold-immune self, wearing a T-shirt during a hike to a high spot above Fels Glacier in the eastern Alaska Range.

“I probably had an ice ax in my hands,” she says.

Dry-Cabin Living

Another version of that frontier life lasted five years for Delamere, who as a PhD student at UAF rented what’s called a “dry cabin” 5 miles north of campus in Goldstream Valley. That meant no indoor toilet and no running water, with electricity for lamp light and a tiny gas stove. Showers and laundromats were available at school.

“It was a popular lifestyle for graduate students,” she says. “The rent was cheap, and the landscape was lovely.”

When the weather allowed it, Delamere rode or pushed a bike to get to campus. Otherwise, she hiked to campus through a patch of forest and over a creek, lighting the way with a battery-powered headlamp and yelling to scare away moose.

In Alaska, male moose, bearded like mad hermits and with horns the size of sails, can grow to 6 feet tall and 8 tons of brush-busting weight.

On the way, Delamere navigated what she called “willow tunnels,” dressed for temperatures that hit 30 degrees below zero.

“I absolutely loved it,” she says.

Cambridge and Colorado

Then love intervened. Delamere moved back East with her husband, Peter Delamere, now a UAF space physicist. He studies solar winds, space plasmas, and auroras, the electrified shimmering polar lights that fan out above the Earth’s high-latitude regions.

They left in 1999 to live in Cambridge and then Lexington, Massachusetts, where Delamere worked with RRTM originator and physicist Eli Mlawer at Atmospheric and Environmental Research (AER).

In 2001, the couple decamped to Boulder, Colorado, where Delamere juggled young motherhood, part-time remote work for AER, and dissertation writing for UAF. She finished her PhD in 2003.

The Boulder chapter, she says, was ragingly busy. Delamere even took on an additional job, eventually, coding for Tech-X, a physics-simulations software company.

Meanwhile, the multistate RRTM team was “fabulous,” says Delamere, with radiation becoming just one component of software that over time “just got better and better and faster and faster.”

‘Better and Better’

In 2012, life itself got better and better and better when the family moved back to Fairbanks for academic jobs at UAF.

“I have this incredible opportunity to see all these scales” at UAF, says Delamere―at the scale of centimeters as an instrument mentor and at the continental scale as director of GINA. “Staring at these beautiful images of Alaska from space, I wouldn’t trade it for anything.”

In summer 2021, she and her family experienced that beauty up close and outside of work. Mother, father, son (Sam, age 20), and daughter (Hannah, age 17) joined two friends (one a wilderness guide and SALVO colleague) for an eight-day backpacking trip in the uninhabited Brooks Range in far-north Alaska.

They flew in on a float plane to the Jago River Valley, backpacked 20 miles or so to the Aichilik River Valley, then traversed the Aichilik River for about 55 miles to the barrier islands of the Beaufort Sea on the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Beaufort Lagoon awaited, still crystalline and frigid with chunks of sea ice.

“It is a vast, vast wilderness,” says Delamere of the landscape. “There were herds of caribou, and muskoxen and wolves.”

Each trekker carried a pack weighing 50 to 80 pounds, stuffed with a tent, food, an inflatable boat, and a paddle. They wore waders for when the water got too shallow for rafting. On their belts were cans of bear spray.

Despite being so many miles inland, the riverbeds revealed abundant fish fossils. The tundra was broken by wave-like heaves of exposed permafrost.

The trip was the dramatic essence of being in Alaska again, this time for life. It was that home-movie dream come true.

For everything, says Delamere, “I thank my lucky stars.”

Keep up with the Atmospheric Observer

Updates on ARM news, events, and opportunities delivered to your inbox

ARM User Profile

ARM welcomes users from all institutions and nations. A free ARM user account is needed to access ARM data.