Editor’s note: Zac Espinosa, a PhD student at the University of Washington, recently participated in an ARM field campaign in Utqiaġvik (formerly Barrow), Alaska. Espinosa wrote the following blog post about his experience.

Looking out across the horizon, it was difficult to tell where the sea ice ended and the sky began. I looked down at my skis, filled my lungs with a deep breath of cold air, and smiled to myself, marveling at my circumstance. I was north of the Arctic Circle skiing on sea ice and navigating melt ponds while towing a 50-pound sled of scientific equipment. How did I, someone who grew up in the suburbs of Chicago, equal distance from a bustling metropolis and the calm Midwestern cornfields, find myself here? I closed my eyes and laughed, thinking if I swapped sea ice for corn, polar bears for coyotes, and near-freezing weather for 100-degree summer days, Utqiaġvik, Alaska, would be just like home. That is to say, about the only thing Illinois and the Arctic have in common is they are both flat.

I graduated from Stanford University in 2021 with an M.S. in applied physics and a B.S. in computer science. The following fall, I started a PhD program in the Department of Atmospheric and Climate Science at the University of Washington. I work with professor Cecilia Bitz, a renowned polar climate scientist, on a variety of research topics related to climate modeling, climate dynamics, and sea ice.

During the third year of my PhD program, I was asked to help with the Snow ALbedo eVOlution (SALVO) field campaign, which is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s ARM user facility and Atmospheric System Research (ASR) program. I was ecstatic … and a bit nervous. I was more accustomed to doing research behind a computer screen in a temperature-regulated office than on a snow machine in the Arctic. But after three years of thinking about polar climate nearly every day, I was excited and ready to finally experience it in person.

SALVO is a research project comprising three field seasons in Utqiaġvik, aimed at collecting detailed albedo measurements of snow on sea ice and tundra during the melt season. Each year, the area surrounding Utqiaġvik, also known as “the top of the world,” experiences a rapid transition from very reflective snow cover to darker tundra and water. Albedo is the ratio of how much sunlight a surface reflects to incoming solar radiation. Surfaces with a high albedo efficiently reflect sunlight and tend to cool their local climate (e.g., snow, sea ice, and thick clouds). In general, warm temperatures reduce snow and sea ice cover, leading to lower surface albedos and more local warming. This positive feedback, known as the ice-albedo feedback, has led to amplified warming in the Arctic relative to lower latitudes.

Scientists, including those participating in SALVO, are working hard to improve our understanding of albedo in the Arctic and better represent the physics related to albedo changes in climate and weather prediction models. This research requires building data sets, such as those generated by SALVO, that incorporate a variety of field measurements, including snow depth, albedo, aerial imagery, sea ice cores, and soil moisture.

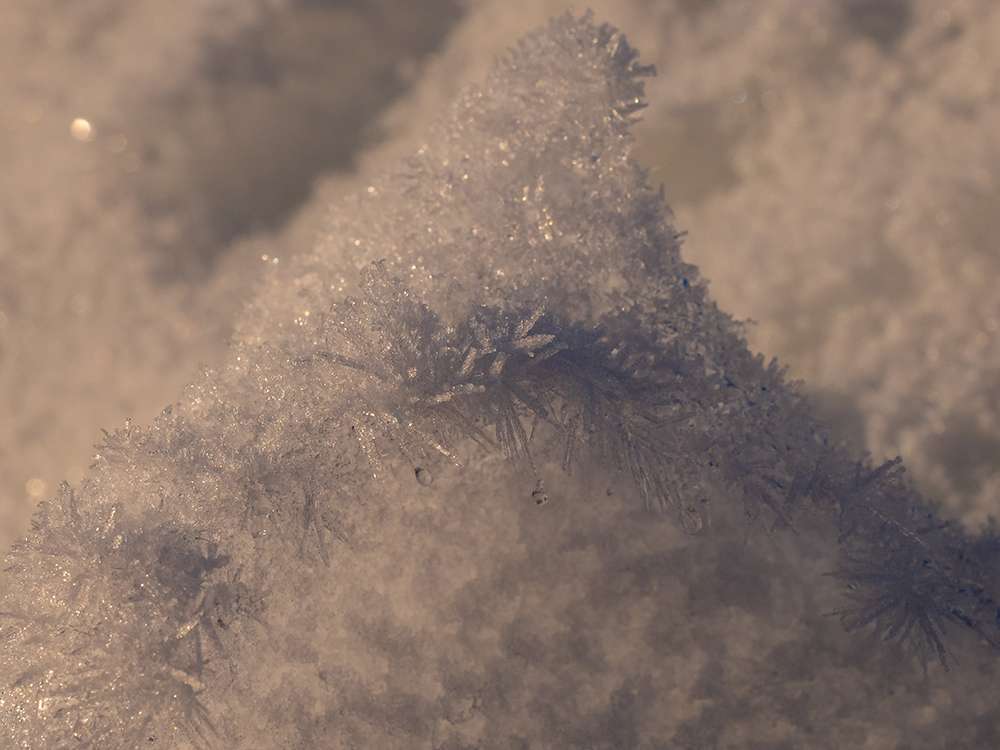

While participating in SALVO, I was fortunate to work with kind and experienced scientists. Twenty-four hours of sunlight meant long days in the field and plenty of learning opportunities. I was consistently shocked and humbled by the speed, beauty, and complexity of the melt season. The tundra and sea ice drastically changed from day to day, dictated by intricate interactions between the atmosphere, topography, vegetation, and snow and sea ice structure.

When we weren’t working in the field, we spent time birding, cooking community dinners, exploring the cultural center, speaking with locals, and visiting the whale bones surrounding town.

I am thankful to have had the opportunity to participate in SALVO’s 2024 field season and to learn from such knowledgeable scientists and community members. We would like to recognize that this ongoing research occurs on Iñupiat land and cannot be completed without the wisdom and generosity of the Utqiaġvik community.

The primary tundra measurement sites for SALVO were located at ARM’s North Slope of Alaska central facility (C1) and extended facility E12. Technical field support was provided by Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico and UIC Science LLC.